Ten Years Later

This is another work in progress, although I don’t expect it to take as long to finish as my State of Faith essay (which still isn’t done). I’ve been thinking a lot about my mental health crash at the end of 2014, and this is how I’m documenting that. While it felt like the end of my world at the time, the changes I had to make in order to recover were the end of a lot of unhealthy thoughts and habits and the beginning of living a much healthier and happier life. Not perfect, but . . . I’m getting ahead of myself. Buckle in folks, it’s gonna be a bumpy ride.

1/29/2025: Latest revisions

The Crash

Ten years ago, on the Saturday before Christmas, 20141 I woke in a state of intense fear. I wasn’t afraid of something; I was afraid of everything and of nothing. Fear choked my lungs and sweated from my pores; I labored for every breath. I couldn’t run; I couldn’t hide; there was nothing to run or hide from. This was neither how I expected nor how I wanted to celebrate the birth of Jesus. It was going to define my life for the next two years.

I had gone to bed the night before finally feeling some calm after a long autumn of debilitating anxiety, recovering from a med change gone bad. I was exhausted and relieved that that awful season was finally over. My mind had other plans. At some point during the night, my brain decompensated, and my mind screamed, “tilt!” You know that twilight period when you aren’t quite asleep anymore, but neither are you awake, and the world is a warm and peaceful place, wrapped in the comfort of soft blankets and still dreaming wonderful dreams? Did. Not. Happen. I jolted awake, in what should have been the comfort of my own bed, instead into a state of hyper-alert terror. Sometimes you can pretend bad things aren’t happening by curling up in a ball and squeezing your eyes shut. No such luck. My body had betrayed me, and no amount of pretending could hide that.

I remember very little of the next few days—a chilly walk at Mendon Ponds Park with my wife, dragging myself to church and breaking down, sobbing, as I asked for prayer, a psychologist friend telling me it would eventually get better, an emergency visit to my psychiatrist, who prescribed an atypical antipsychotic and told me it should start to take effect in about three days. Then, Christmas with friends at their parents’, sharing a festive meal in a fog.

The antipsychotic worked and brought my anxiety down to a tolerable level within a week or so, but then the insomnia started. Regardless of how desperately you might want to, you can’t make yourself go to sleep. You can’t relax harder. Every night I would lie in bed, willing my body to give up. Finally, after a protracted twilight daze, I would fall into a shallow sleep for a few hours, groggily awake, stagger through my morning routine, and drive to work.

I tried to maintain a normal life—somehow during this time I managed to begin an evening photography class and start to build a portfolio. The dates on my photos are proof, but I’m baffled how I had enough energy to do it. I remember fretting about getting home promptly because I was already pushing my bedtime—insomnia triggered persistent anxiety over my need for sleep. Constant fatigue due to sleep deprivation grew worse. In the afternoons, I collapsed on the couch and curled up under blankets, trying to make up for the sleep that refused to come at night. I struggled through each evening, then began the cycle again.

After three months of growing exhaustion, I collapsed at a med check. As I struggled to describe my suicidal thoughts through heaving sobs, my psychiatrist asked me if I could safely drive myself to the hospital. This was my proverbial rock bottom. While I wasn’t actively making plans to end my life, it was starting to look reasonable. It’s hard to convey how hopeless I felt and how badly I wanted the pain to stop. Suicide is rarely, if ever, a rational option, and I was definitely not rational. I had thought about how to do it (I was a little bit rational), which is why my psychiatrist sent me to the ED immediately.

I spent that night in the observation unit of the psychiatric ED at the hospital where I worked, then spent the next nine days on a locked inpatient unit. My windowless room was equipped with breakaway clothing hooks and an inspection glass in the door, and I wore sweats without drawstrings so I couldn’t harm myself. Concerned medical professionals asked me lots of questions and devised a new cocktail of meds that would relieve my anxiety while letting me sleep. Thirty minutes after my first dose, I couldn’t keep my eyes open. I just wanted to sit alone and read a book but was “encouraged” to attend daily group therapy sessions and arts & crafts time, where we carefully filled geometric patterns with brightly colored pencils. It wasn’t basket weaving, but it served the same purpose: keeping my mind focused on something other than how hopelessly shitty my life had become, while the meds gradually did their work. After a week, I was allowed to put on my civvies and attend a nearby day treatment program. Coming back to the hospital felt like reentering prison, and I was both relieved and disoriented when I was finally discharged into the care of my wife at home. I finished out my two weeks in the partial hospitalization program, then it was back to work and normal life, or as normal as I could manage.

Recovery 1.0

My memories of the next few months are fuzzy, but I have a photographic record2 (I document everything), and I still have my calendar entries from then. Looking back, I was more active than I remembered. Clearly, I was fighting, trying to get better. I finished my photography class and went to a baby shower. My brothers and I finally buried my dad’s ashes on July 16, oddly enough, also my daughter’s birthday. I lasted until early August, when a social worker colleague found me, exhausted and unable to form a coherent sentence, sitting in the staff elevator lobby of the children’s hospital.3 She fetched my wife, who brought me back to the Psych ED. My psychiatrist was on service and admitted me to the partial hospitalization program again, after which he put me on three months of disability.

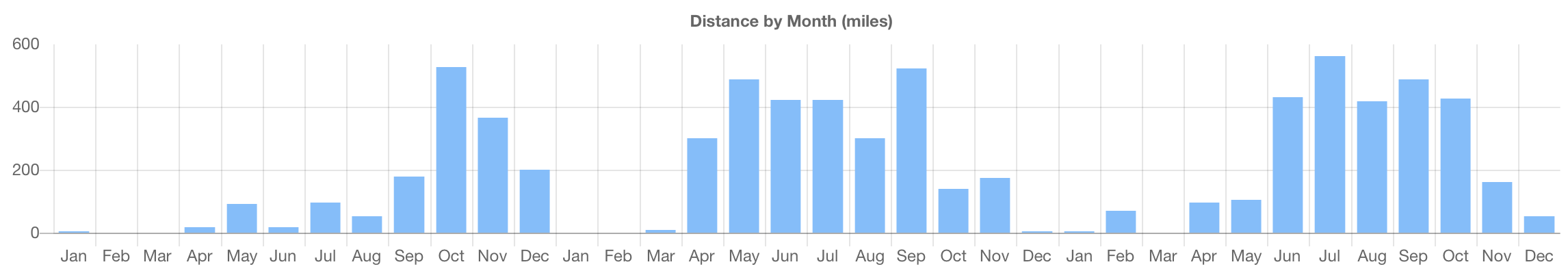

I don’t remember this period clearly either, but I’ve looked back at my workout tracker from that time (remember, I document everything), and this is when my riding took off. In August, I rode four times and logged 52 miles (about 13 miles per ride). We visited the Corning Museum of Glass and brought our daughter to her freshman year at RIT. In September, I rode 10 times and logged 181 miles (about 18 miles per ride). I started weekly pizza lunches with a friend from church, and we took pictures together near his office. In October, I rode 25 times (6 days per week) and rode logged 526 miles (about 21 miles per ride), including a 60 mile ride on the canal. We went to our church’s annual Cider Days, and I volunteered as a photographer for a cancer support group’s 5K fundraiser and our church’s Halloween trick or treat. My riding tailed off some in November and December but we made it to Virginia for a family thanksgiving, including a trip to the Jamestown Settlement living museum. my wife and I rode the canal on a 40º December 26, the coldest ride I’d ever taken. I picked up again the following April and stayed consistent until the next winter. Even during the cold weather, I was using an elliptical and bike trainer almost every day. Eventually I worked up to 25 or 30 miles per day, six or seven days per week. I rode from home to the Erie Canal trail, then to Fairport or Genesee Valley Park, or I rode up to Lake Ontario and over to the Genesee River where it flowed into the lake. I lost weight and gained endurance, and you could break rocks on my thighs. I returned to work for another several months, then, exhausted, went on another three months of disability and even longer bike rides. Two years after my crash, I was weaned off all my crisis meds but one (at a low dose) and finally felt like this was a new normal. Along with meds, therapy, and rest, and supportive relationships, I had ridden myself out of severe anxiety and depression.

The Lead Up

My crash didn’t come from out of nowhere. I’ve struggled with depression most of my life, and over four decades of work on my emotional health have given me a clearer perspective as to where it came from and the ability to analyze it more objectively. I now believe the root causes were anxiety, which has a genetic component, persistent bullying, and weak inherited social skills. These produced anger, depression, and shame. I used to think my anger and depression were the causes, but I believe now those were only symptoms. Fearing my anger and trying to shut it down simply caused depression and more anger that erupted unpredictably.

While my problems developed over many years, I can trace their origins to childhood:

- Starting in third grade, I was persistently bullied in ways that wouldn’t be tolerated now. This change was triggered by the arrival of some students who formed the cult of Dave (an athletic classmate, who was actually a good guy), and as a nerd, I was excluded. A few problem kids harassed me at school and and even church without consequence (many attended both). Adults saw it and failed to act.4 To the contrary, they saw my justifiable anger and blamed me, labeling it as a temper that I had to learn to control.

- I was raised by geeks, which is a bit like being raised by wolves, except that wolves are pack animals and probably have better social skills. Dad loved us, but he was clueless as to how to express that, having come from a dysfunctional family. Mom was more demonstrative but could be passive—her NYC attitude was constrained by the religious and social mores surrounding her.

- Our family suffered from a version of midwest nice—blend in, don’t complain, take what you’re given, you’re not so great after all, don’t ask for anything, don’t rise above your station, don’t expect much.

- Our church’s Reformed theology, which taught we were born sinful and were utterly incapable of doing good, was poor soil for growing healthy self esteem. I never much enjoyed the church version of Scouts or youth group, and the one place I felt at home was the adult church choir.

- I was smart, but smart wasn’t cool. Professor was what kids called people they thought were weenies and wimps. In response, I looked down on kids I thought were anti-intellectual5 to preserve my self respect.

- Anxiety . . . where do I start? I obsessed on perceived failures and embarrassments and had no hope of reaching the impossibly high bar I set for myself.

- Failures were always my fault, due to my glaring defects.

- Trying to fit in made my brain hurt and heart ache.

- I felt powerless against bullies.

- My anxiety often looked like fear of my own anger. I was afraid of conflict to begin with, and fear of losing control made me tolerate awful conditions to maintain the appearance of peace and calm. Control kept me safe and adult-approved.

- Anxiety hurts. I carried it in my body, constantly cramping my back and raising my shoulders. When I noticed and lowered them, they would go back up as soon as my attention went elsewhere.

- Shame. This one hurt the worst, and it was always waiting to kick me when I was down. I was ridiculed and excluded, then blamed when that made me angry. It became clear to me that I was the problem—I was a defective human. It’s not as bad now, but I still get hot flashes when I recall embarrassments from fifty years ago. I fought back, finding ways to prove myself—being smart, being kind, being helpful. These helped, but ultimately they were only holding back the beast. I couldn’t banish it; I couldn’t beat it.

Graduating from a small Christian grade school and and moving to a large public high school was a shock to my system initially but longer term gave me room to be much more myself. I was less angry, but it still could burst out even I was was trying mightily to control it. I felt less anxious and more lonely. I obsessed on girls I liked but lacked confidence. Frustration at my social impotence turned inward and became depression. Yes, I know I was an adolescent nerd, but it felt like I was alone in my failure. It also led to me think that depression was the root cause of my mental health issues rather than anxiety. Still, I was able to find other nerds, and that was a relief.

College was a huge change. I enjoyed my independence and the intellectual atmosphere, but I developed intense anxiety about keeping up with classwork. I had learned zero study skills in high school, and I spent most of my free time at the radio station during my freshman and sophomore years. Writing papers paralyzed me, and I simply didn’t write them. That did a number on my grades. My junior year, I was on academic probation and stopped hanging out at the radio station, which helped me finally develop some consistent study habits. I had failed a course taught by my favorite professor, and I think I buckled down as much to please him as to get better grades—I aced every course of his that I took from then on. Oddly enough, I was able to use my obsessive concentration to memorize lines for plays, in spite of anxiety and procrastination. That skill could have taken me far in other classes had I learned to apply it. Writing never got easier until my sixties, when I ditched my expectations and started simply to write what came to me. It wasn’t bad, and I could edit.

Romance still eluded me. I had summer flings at the camp where I worked, which I fruitlessly tried to stretch past their expiration date. I fell hard for a classmate who returned my affections and spent a brief, intense semester doing everything together. That ended suddenly when she dumped me after I met her parents and apparently didn’t pass muster. I don’t remember exactly how long I pined after her, but it was awful. I finally resolved to stop making myself miserable after a summer away, but I was still struggling enough to seek out help from the college counseling center. That was the first time I was formally diagnosed with depression.

With that, I started, gradually, down the path to mental health. I’d come from a family that didn’t do emotions and had a lot to learn, so I took self help classes and saw different therapists, looking for a good fit. Thankfully, I found one who has remained a friend and counselor for nearly 40 years. I did have close friendships and married, albeit ten years later later than my siblings. I was making progress, but I’d only started on what you might guess has been a long journey. You’d be right.

Adulting proved difficult, and I struggled to find fulfilling work, probably staying too long at frustrating jobs because I didn’t have the skills to negotiate or the confidence to leave. In the 90s, I jumped at the chance to move from IT into media and graphic design. I ended up at a small studio, where I thrived but bumped heads with management. Then 9/11 happened, and the advertising world went to pieces. I tried to leave calmly, I really did, but bottled up frustration exploded again. I looked for work elsewhere, but the market had dried up, so I tried freelance and failed. I gave up on full time work and took over as parent at home for eight years—I’m grateful for that time with my daughters while they were in elementary school, but it was rough on my ego and rough on my marriage.

I didn’t give up looking entirely, and when the girls became more independent, I finally landed a job working as a representative for a software vendor at the University of Rochester Medical Center. My customer loved me, but my supervisor said I wasn’t pushing corporate strategy hard enough. We finally resolved that by splitting the position, and I became a medical center employee but at only half time. I thought this would be transitional, but I wasn’t able to find work elsewhere—once again, I felt frustrated by my failure and lack of drive. The system I supported went though a series of changes in sponsorship, and I became irrelevant. I felt useless and isolated, working in a tiny office with no real colleagues, and my mood sank lower and lower.

My psychiatrist tried several medications to boost my energy, and the last of these changes inadvertently cut off my antidepressant cold turkey (the new med didn’t work). Don’t try this at home—the crash was ugly. At my next checkup, my psychiatrist immediately put me back on my old med, but I had to wait through the fall for it to build back up in my system. November was the one year anniversary of my dad’s death, which had left me spent after years of family drama. Looking back now, I believe that must have affected me. By my daughter’s 18th birthday party in mid-December, I was exhausted after suffering through months of largely untreated anxiety, but it seemed I was finally functional again and could move forward. I had no idea how mistaken I was.

Recovery 2.0

End of flashback. Back to recovery.

Mental illness had destroyed the shaky equilibrium I’d patched together with meds and avoidant behavior, but I’d done the work and built my life back to where I was functional and stable. Now I needed to continue to build a life that wouldn’t drag me back down into exhaustion and depression. Using the skills and confidence I’d learned in recovery, I was able to confront and solve problems instead of painfully limping through impossible conditions. Conflict was still scary but far better than going back to where I’d been. I had finally learned deep down that my deep and abiding shame was a lie. I wasn’t worthless. I wasn’t incompetent. I wasn’t defective.

So, what changed?

First, like any good patient in cognitive-behavioral therapy, I changed my unhealthy and self-defeating cognitive distortions. Five points for counseling-speak, but what does that really mean?

At age 52, I’d already made a lot of corrections to the cognitive bits. I’d been in counseling on and off since college, and I didn’t think I was worthless; however, I still felt worthless. While my Calvinist upbringing might have tried to teach me that feelings were not to be trusted (partly true) and that they could be changed simply by thinking right thoughts (a tiny bit true), it turns out that feelings mostly lead thoughts, not the other way around. Both thoughts and feelings drive behavior, but feelings are the elephant, and thoughts are the rider.6 It’s possible for thoughts to change feelings, but it takes a lot of time and a lot of effort.

It also turns out that changing behavior can change feelings. If we act like a thing is true, our emotions will eventually follow. When I started acting like I was worth something and could accomplish goals, I started to believe that. I actually was accomplishing my goals, which made it a lot harder to feel, much less believe, that I couldn’t. This helped develop the confidence that had long evaded me. You might hope for a more intrinsic sense of worth, but even transactional self worth was a big improvement. It certainly was better than thinking I was better off dead.

I was acting like I was capable and worthy, and that changed my emotions and thoughts. So, what enabled me to change my actions? Simply put, I was pissed off. I had hit bottom and didn’t care what anyone else thought—they couldn’t put me through anything worse than what I’d just been through. While out on disability, my only responsibilities were eating, sleeping, and occasional bathing. Getting out of bed was a life goal, and I could manage that.

I had time enough to do whatever I wanted, and my go-to activity was one I’d loved since I was a kid—riding my bike. As I said above, this wasn’t riding around the block or to the grocery store. It was riding hard for two hours, up and down steep hills and along the Erie Canal. It was 30 mile rides to towns I rarely visited in a car, then riding 30 miles back. Rides that turned my legs to jelly and made me fall asleep as soon as my head hit the pillow—a welcome side effect, given that I was still anxious about my ability to sleep. If you’ve been so exhausted from insomnia that suicide seemed like a reasonable alternative, trust me, you worry about sleeping, and every night of good sleep put that fear further behind me.

Being pissed off finally pushed me into action. I decided, screw it, I’m going to do the things I’ve wanted to for decades but was afraid to try. I started taking cello lessons for the first time since college. I actually practiced. I took pictures on walks around my neighborhood and entered them in shows. Eventually, I bought a better camera and started volunteering as a photographer at the zoo. I bought a better photo editor, and my technique improved by leaps and bounds. I started setting boundaries and enforcing them, which was a bit of a shock to people around me. I wasn’t obnoxious (for the most part), but I wouldn’t let people walk on me.

I repaired stuff at home, and I hired contractors to do the stuff I couldn’t, didn’t have the energy to do, or just plain disliked. Stuff was getting done, and I liked it. I was a better dad because I liked myself and could be patient with my teenaged children. I was happier at work because I wasn’t always hoping to be delivered from a job I disliked—I found ways to enjoy the work I was doing. My supervisor recognized I’d been underutilized (aka, bored out of my mind) and gave me more to do. I moved from an office where I was isolated and alone to a cube farm where I was surrounded by other people. Yep, you read right, a cube farm improved my mental health.

In a way I was like Dorothy, and I’d had what I needed the whole time. I had a brain and a heart and courage but didn’t know it. I just needed to click my heels three times and do all the things that healthy people do—hitting bottom forced me into that. I decided there was no way I was going to stay down there, and I acted on it.

Ken 2.0

My wife now calls me Ken 2.0, and it’s a mostly positive assessment of the changes in my personality and behavior since my crash and recovery. Because she doesn’t live in my head, she notices changes in my behavior most—a few examples:

- The first thing she noticed was the boundaries. If I felt she was being unfair or mistreating me, I’d tell her, and I wouldn’t let her blame me for things that weren’t my fault. I tried not to to be unfair myself, but I called out behavior that made me say, “ouch”.

- I stopped apologizing for asking her to do things for me. I used to cringe when I asked her to scratch my back (my all-time favorite form of affection) because I had been conditioned to expect an annoyed response. Now I just ask, and if she can’t or doesn’t have enough energy, that’s fine.

- I’ve become much better at managing and regulating my emotions. Because I’ve grown more assertive, I address problems and annoyances before they can grow into huge issues in my mind and trigger disproportionate responses.

- Recently, due to a series of unforeseen events, we needed to purchase two cars in the space of three weeks. While that was stressful and tiring, I was able to respond and be helpful rather than becoming overwhelmed. My wife noticed.

- I’m taking better care of myself. I eat better (although I still have a weakness for sweets), and biking has become an integral part of my life.

- My network of friends has grown, and I talk to them more often.

- I’ve learned how to use a todo list effectively. It isn’t a taskmaster running my life but a trusted system for capturing my thoughts—this relieves my anxiety over forgetting what I need to do. It also makes me significantly more productive.

- As witnessed by this essay, I process through writing, which is a massively helpful relief valve.

My wife has noticed growth in her life in many of the same areas, I hope, inspired some by my growth. This is an educated guess, but I believe my newfound ability to work through problems more matter-of-factly and without so much defensiveness and anxiety has both reduced her defensiveness toward me and provided a positive example. We’re both mature and emotionally intelligent adults, but those qualities have been inhibited in the past by deeply ingrained unhelpful responses to each other. We were stuck in bad habits and needed to be forced out of our learned ways of being in order to break those habits. Hitting rock bottom emotionally and physically was the big stick for me.

So, have I arrived? Sort of. It’s axiomatic in mental healthcare that depression doesn’t just go away but requires lifelong management. I’m functional and I enjoy life, mostly, but I know I can’t just stay there—I need to proactively protect my mental and physical health. That means I get enough sleep and nap if I need to. I have become a bicycle commuter and get plenty of physical exercise. I talk to friends. I exercise my brain. I recognize when I’m anxious, but I don’t become anxious about my anxiety—that leads to a downward spiral and crash if you let it. I confront problems before they become unmanageable. I work through problems instead of suffering in silence.

Epilogue

I took the photo at the beginning of this essay on a lunch break, behind the building where I was yet again in partial hospitalization. At the time I thought it was just a pretty picture, but since then the imagery of the bent and broken blade of grass being supported by the grass surrounding it has taken on deeper meaning. I didn’t, I couldn’t recover on my own. I was supported, carried at times, by my community, and now I try to do the same for others who are struggling or in crisis. That’s why I wrote and why I share this essay. I hope that we may lose our fear of sharing our own pain and walk the path of healing alongside those who cannot walk it on their own.

-

December 20–Christmas was the following Thursday. ↩︎

-

In particular, on a lunch break from my second time in partial hospitalization, I took a photo of marsh grass behind the parking lot (shown at the top of this essay). One long blade is bent over at a 90º angle but still standing because it is supported by other blades. We use that as a song background at church, and it is at the head of this essay. It always reminds me of how far I’ve come. ↩︎

-

I do remember that this was around the time that the children’s hospital moved to the new tower, and I had to clear out a large number of televisions from the old units, so that renovations could begin. I was entirely on my own and can remember struggling against extreme fatigue to pile TVs onto carts and dump cables into garbage bags, then stuff them all into a small room where TVs were stored. I grabbed spare trashcans to store parts, only to find them dumped out because, apparently, trashcans were like gold, and I couldn’t take them. ↩︎

-

Mom saw the bullying but lacked the training to recognize and treat anxiety, and she felt constrained from acting against bullies. Protecting her own child would have been completely normal, but she was likely correct that it would have been labelled as favoritism, and a small, Christian school was hostage to influential parents who could complain loudly, withdraw their children, or simply not pay. This being the early seventies in a Reformed religious community, cultural mores also constrained her from speaking out because she was a woman. Bullying was finally recognized as a serious problem in the 90s (?), but kids still kill themselves because they can no longer take the pain. I’m alive, but I bear scars. ↩︎

-

Yeah, I probably used that term. I was a massive nerd, and I was reading several years above my grade level. ↩︎

-

This is the central premise of The Righteous Mind by Jonathan Haidt. ↩︎